Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) and the B-2 Bomber

PAUC can be dramatically affected by how many units of the weapon system are purchased, as well as development cost increases - the B-2 is perhaps the most famous example of this.

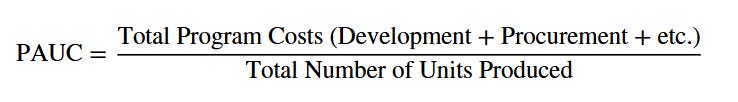

The Program Acquisition Unit Cost (PAUC) for a weapon system can vary dramatically because it is calculated by dividing the total program cost (which includes large, one-time development costs) by the total number of units produced.

PAUC=(Total Program Costs (Development + Procurement + etc.) over the total Number of Units Produced

The relationship between development costs, production quantity, and the resulting PAUC is driven by the concepts of fixed costs (primarily development) and economies of scale.

Impact of Development Costs

Development costs, which include Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E) and other non-recurring engineering expenses, are essentially fixed costs for the program. These costs must be incurred regardless of how many units are eventually built. However, it is common for these costs to go up over the life of the program, which drives up the PAUC in most cases.

Higher Development Costs = Higher PAUC (if quantity is fixed): If a weapon system has an extensive, expensive, and complex development phase, these significant upfront costs are baked into the “Total Program Costs” numerator.

Added Development during Production: If more development work is needed and added to the program after initial planning (e.g., to add new capabilities or fix issues), the total development cost increases, directly driving up the PAUC.

However, if the extra development cost actually resulted in a design change that makes the weapon system cheaper to build, it could actually result in the PAUC going down.

The number of units produced serves as the denominator in the PAUC calculation. This creates a critical leverage effect, rooted in the principle of economies of scale:

Spreading Fixed Costs: The large, fixed development costs are spread out over the number of units produced. The more units built, the smaller the portion of the development cost assigned to each individual unit.

Lower Quantities = Dramatically Higher PAUC:

If the number of units built is low, the large fixed development costs are divided among very few items, resulting in a very high PAUC (the cost per unit is high).

Reducing the production quantity mid-program can significantly increase the PAUC, sometimes triggering mandatory reports to Congress due to unit cost breaches (known as Nunn-McCurdy breaches).

Higher Quantities = Lower PAUC:

If a program produces a large number of units, the fixed development expenses are spread thin across all units, leading to a much lower PAUC.

THE B-2 BOMBER PROGRAM AND PAUC

As is often the case with U.S. weapons programs, the decsion to lower B-2 bomber production from 132 to 21 was driven by development costs greatly exceeding their original estimated $15B, growing to $24B. This, plus the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the belief that a bomber like the B-2 was no longer as important sans Soviet Union, led to the radical 86 percent reduction in B-2 production numbers. That drove the B-2’s PAUC to $2 billion plus each. However with development costs being about $24 billion, the average price to actually build the planes was “only” about $950 to $980 million, and because of process improvenents and learning curve effects, by the time the 21st B-2 rolled out of the factory in 2000, the incremental/flyawway cost for building B-2s had dropped to $737 million. A1990 La Times article quoted an Air Force official who claimed that an additional 60 planes would results in a per plane flyaway cost of $457 million ($926 million 2025 USD). Whether or not B-2s could have gotten down to “just'“ $457 million will never be known, but even at $926 million USD 2025, they are crazy expensive.